Powertech Uranium Corp. has received a critical regulatory approval for its Dewey-Burdock project in South Dakota, the company announced Tuesday. nuclearstreet.com

The Nucleotidings Blog

The Nucleotidings blog is a writing platform where Burt Webb shares his thoughts, information, and analysis on nuclear issues. The blog is dedicated to covering news and ideas related to nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and radiation protection. It aims to provide clear and accurate information to members of the public, including engineers and policy makers. Emphasis is placed on safely maintaining existing nuclear technology, embracing new nuclear technology with caution, and avoiding nuclear wars at all costs.

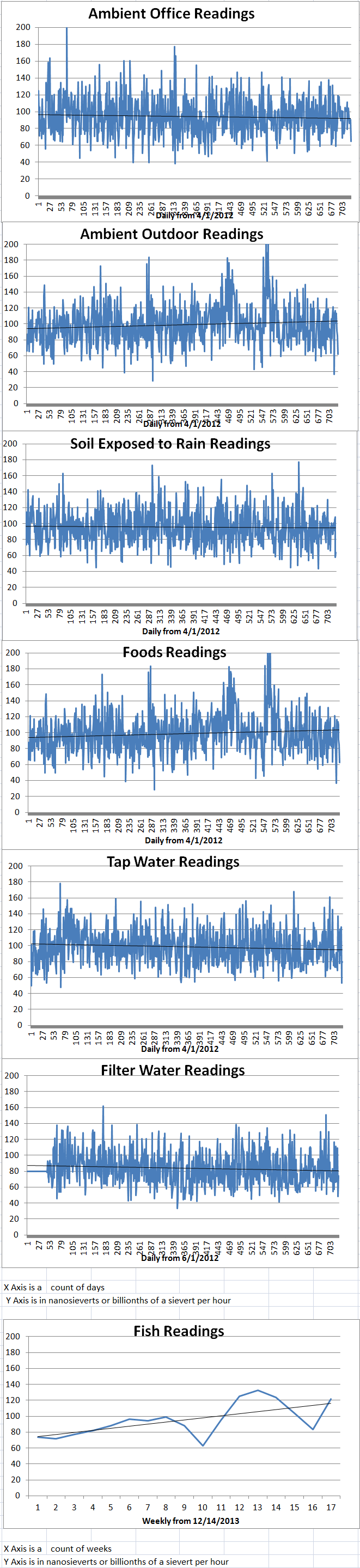

Your Host: Burt Webb

Burt Webb is a software engineer, science geek, author, and expert in nuclear science. Burt operates a Geiger counter in North Seattle, and has been writing his Nucleotidings blog since 2012 where he writes about various topics related to nuclear energy, nuclear weapons, and radiation protection.

Burt Webb has published several technical books and novels. He works as a software consultant.

Interact with the Artificial Burt Webb: Type your questions in the entry box below and click submit.

Example Q&A with the Artificial Burt Webb

Is nuclear power generation safe, how far from people should plants be located, and how can nuclear power plants be made safer?

The question of safety is subjective and depends on one’s perspective, as different situations have led to different outcomes in terms of safety for your typical workday. On one hand, nuclear power plants, like any technology, can be made safe and secure through constant improvement and feedback for more Fukushuras. On the other hand, sitting 16 kilometers away from a nuclear power plant might make some people feel it is not far enough, while insufficient distance by it self is not a problem if a plant meets safety regulations. Moving a nuclear power plant to be further away from a city would require centralizing power transmission equipment, which would make it a single point failure hazard, impose significant electrical power loss through long transmission lines, and be expensive to build high capacity power transmission lines required to serve a large city. Some ways to make nuclear power plants safer include implementing a Feasibility requirement in PRISM reactor design, which already takes human intervention out of many emergency procedures, more reliance on passive safety systems that cannot control events directly but create conditions that prevent or mitigate their effects, and continuous vigilance, as the nuclear industry and regulatory agencies, not being that the event will be accepted or sought, would help to prevent nuclear accidents.

What do you mean by “Fukushuras”?

“Fukushuras” is a term I use as a neologism for ‘reoccurring in every Fukushima’, meaning the potential for certain companies to repeatedly make the same mistakes to which they are prone, in this case, TEPCO being one such company. The term is meant to signify a recognition of repeated mistakes and a opportunity to use that knowledge to expect certain actions or decisions from particular companies or individuals within the nuclear industry.

I have blogged about a lot of nuclear accidents both large and small. I have often said that if there is one more major nuclear accident in the world, it could seriously damage the reputation of nuclear power. Politicians, investors and the public at large will be much less inclined to support the construction of new reactors. And, given the realities of the nuclear industry, it is inevitable that there will be another major nuclear accident.

There have been three major nuclear accidents in the past thirty five years including Three Mile Island in 1979, Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011. That averages out to about one about every twelve years. The number of accidents might be small compared to the number of operating reactors but each caused environmental damage. Two of them generated radioactive contamination that spread far beyond the country where the accident occurred. The cleanup of Chernobyl and Fukushima continue, absorbing billions of dollars and may never be completed.

I am certain that no matter what the nuclear regulatory agencies and nuclear corporations do, there will be another major accident in a few years. While I fully support the efforts of the regulators and manufacturers of nuclear reactors to make them as safe as possible, perhaps more thought should be given to what to do when an accident does occur. One major lesson from Fukushima is that the Japanese were ill prepared to deal with a nuclear emergency.

Currently there are one hundred and seventy six new nuclear reactors being planned across the globe. Over half of those reactors will be built in countries that had no nuclear reactors twenty years ago. If countries that have had nuclear power for fifty years and more have problems regulating reactor construction and operation properly, what chance do countries who are new to nuclear power have if confronted with a major nuclear accident? And it is not enough for the nuclear power industry to have plans to deal with nuclear accidents when the public is ill-informed and ill-prepared.

A great deal of the design of nuclear power plants has been focused on backups, emergency systems, passive response systems that require no human action, containment, and other measure to reduce the possibility of a core melt down. There are still calls for the nuclear industry to do more to insure that if there is another major nuclear accident, the radioactive contamination will not be allowed spread beyond the nuclear power station where the accident occurs. The nuclear regulators and manufacturers claim that the probability of a major accident is extremely low. There is a fear that preparations to deal with a major nuclear accident may have been insufficient because they are not supposed to happen. However, history shows us that however improbably major nuclear accidents might be in theory, they still happen and must be dealt with.

The bottom line is the bottom line. The cost of manufacturing nuclear plants that could contain any possible accident would be prohibitively expensive. On the other hand, a major nuclear accident is enormously expensive. This problem has no solution. Another major nuclear accident might well result in calls for additional safe guards that would make nuclear power uncompetitive. We have the choice of starting the phase out of nuclear power now or waiting until another major accident destroys the ability of nuclear power to compete in the market place. The longer we wait, the greater the cost will be in terms of lives and money.

Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station:

One of the most frightening dangers that nuclear reactors face is the possibility of a nearby earthquake. Containment domes could crack, reactor cores could be severely damaged and melt down, spent fuel pools could be emptied and expose fuel rods to the open air, etc. The ability of the design of a particular reactor to withstand possible earthquakes in the vicinity is very important with respect to licensing the site of a nuclear reactor.

When the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant was built in San Luis Obispo County, California, the design had to be modified to take into account four faults in the area. The plant was hardened so that it would be able to withstand a 6.75 magnitude quake. In 2008, Pacific Gas & Electric documented the existence of another fault just offshore from the power plant. There were calls for upgrading the plant to be able to withstand a 7.5 magnitude quake but PG&E said that they felt that the plant was safe enough for the time being. A study by the NRC published in 2010 placed the annual probability of a quake strong enough to damage the Diablo Canyon reactors cores was about one in twenty four thousand.

In March of 2011, an offshore quake near Fukushima, Japan destroyed the Fukushima nuclear power plant, causing three of the six reactors to experience a core meltdown. Following the Fukushima disaster, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) issued a report that recommended that the ability of the reactors in the U.S. to withstand a quake and/or tsunami be studied and that vulnerable reactors be strengthened where necessary.

As of 2014, the NRC is assuming that U.S. reactors do not pose any immediate risk with respect to possible earthquakes. There have been calls for more studies on the earthquake risk of the U.S. reactor fleet but there does not seem to be a push at the NRC for any immediate work to upgrade at-risk reactors to new earthquake resistant standards. Some members of the U.S. Senate are calling for immediate redesign and upgrading of vulnerable reactors.

Recent seismological studies have indicated that the dangers of a major quake that could shake the ground enough to threaten major components of a U.S. nuclear reactor are greater than previously thought at some sites but not as great as previously thought at other sites. One estimate is that about twenty four out of the one hundred U.S. power reactors are at greater risk from earthquakes than previously thought.

Operators of some of the more problematic reactors are resistant to expensive analyzes and new construction work to meet the new standards. They suggest that the risk is not great enough to warrant the cost of rebuilding. They may be right but if they are only wrong once, the results could be catastrophic. With so many reactors in highly populated areas, a major nuclear accident could cost billions of dollars and impact public health and the environment.

clear power is having trouble competing in the energy marketplace due to cheap natural gas and expansion of alternative renewable energy sources. The NRC has rules that say if a operator cannot make a profit on selling nuclear power, they will lose their license. One major accident at a nuclear power plant in the U.S. would result in a public movement to shut all nuclear power reactors. The cost of nuclear power would rise and power plants might lose their licenses. It appears to me that we have a choice of starting to phase out nuclear power now or waiting for a major nuclear accident to trigger an expensive emergency shutdown of many U.S. reactors.

Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant: