On January 24, 2011 a new rule was put in place by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission with respect to the storage of spent nuclear fuel. The new rule covered the storage of spent nuclear fuel in pools near the reactor, onsite in temporary storage casks or offsite in independent storage facilities. The NRC made changes in 1990 to the Waste Confidence rulemaking procedures to allow for the extension of temporary storage. The new Waste Confidence report included the following five findings.

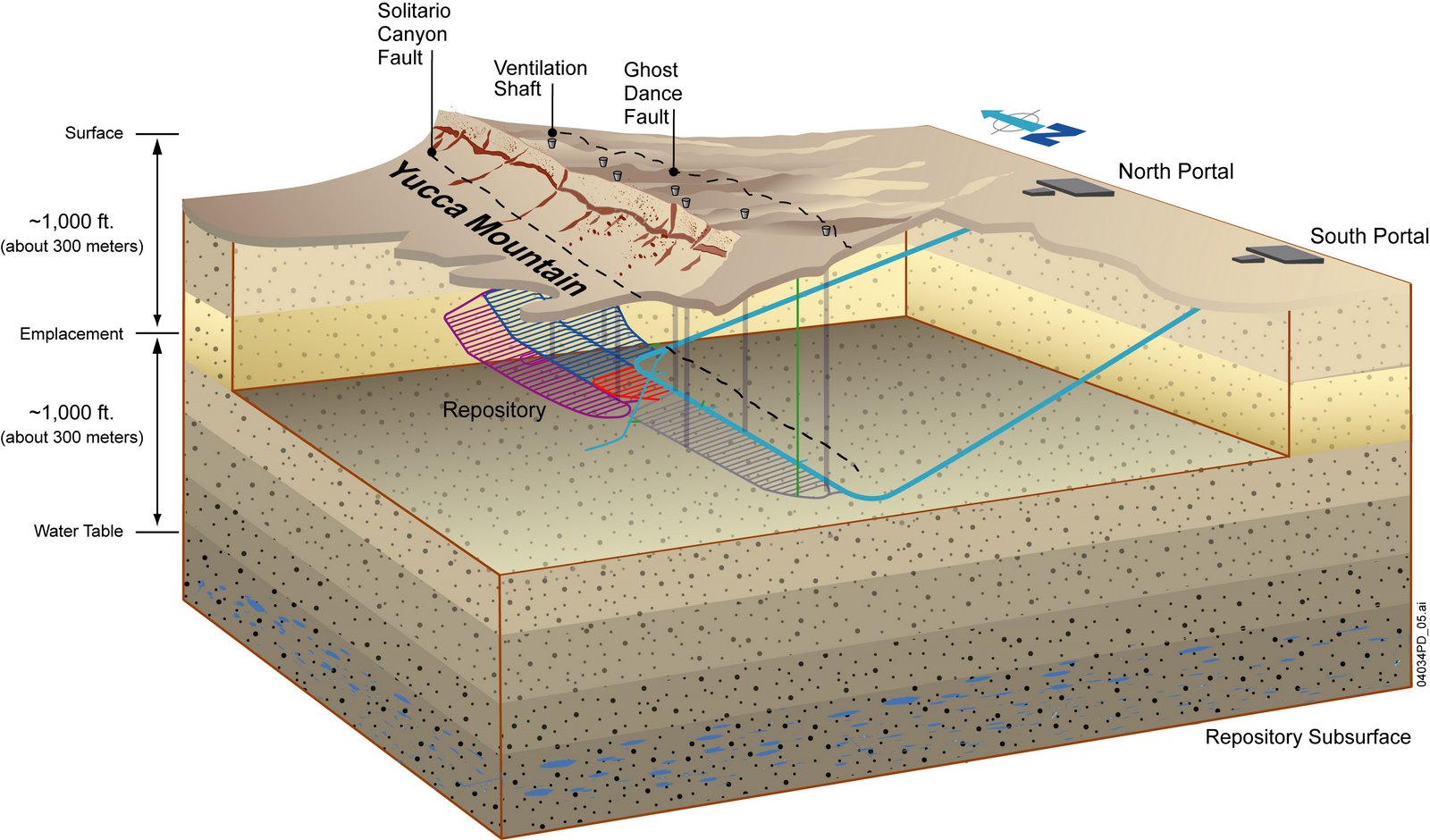

- The Commission found that there is “reasonable assurance” that safe disposal of high-level radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel in a geologic repository is technically feasible. While this may be true in theory, finding a safe repository site has turned out to be difficult to say the least.

- The Commission found that there is “reasonable assurance” that at least one such repository will be available in the United States by the year 2025 and that there will be sufficient capacity within thirty years beyond the licensed life of any operating reactor to accept all the waste generated by such reactors. Considering that the Yucca Mountain Repository was cancelled in 2010 and that it is estimated that it may take twenty years or more to site and develop a repository, it would appear that we are already behind schedule.

- The Commission found that there is “reasonable assurance” that safe temporary storage of nuclear waste and spent fuel will be carried out until the repository is available. We can only hope that this is true.

- The Commission found that there is “reasonable assurance” that until the repository is ready, waste and spent fuel can be stored safely for up to thirty years beyond the licensed life of thirty years for any reactor without adverse environmental impact. This means that the NRC feels that it is reasonable to allow temporary nuclear waste and spend fuel storage for up to sixty years.

- The Commission found that there is “reasonable assurance” that safe temporary onsite or offsite storage will be made available if needed. This better be true because it is estimated that at current levels of spent nuclear fuel generation, all the spent fuel pools in the United States reactors will be full by 2017.

In 1999, the NRC reviewed the findings from the Waste Confidence study of 1990 and concluded that experience with nuclear waste storage since 1990 had basically validated the 1990 findings. Therefore the NRC decided that it was not necessary to carry out a comprehensive reevaluation of its 1990 findings. It further stated that it would consider such a reevaluation after the current repository developments and regulatory activities had been completed. Or, of course, if there were serious unforeseen events at some time in the future. Well, the Yucca Mountain Repository has been cancelled and there was that disaster at Fukushima. The Unit 4 spent fuel pool at Fukushima is a threat to the whole world right now. Perhaps that reevaluation is now due.