Part 2 of 3 Parts (Please read Part 1 first)

While U.S. officials value ambiguity in nuclear weapons policy to allow the president a range of options (and to avoid endless policy debates), the prevailing theory in S.K. is that this kind of ambiguity weakens deterrence and signals wavering commitment from the U.S. However, the U.S. would never make this commitment. The U.S. president reserves the right to decide on nuclear weapons deployment in a specific situation because they would like to consider an array of important factors specific to the crisis. They would almost certainly prefer to find an effective alternative to the use of nuclear weapons. They would also want to consider S.K.’s preferences which may disapprove of U.S. nuclear use on the peninsula, especially under another president. When he was inevitably rebuffed, S.K.’s President Yoon Suk Yeol apparently stated his preferred policy on behalf of the alliance at the White House. He wanted to bluff with U.S. nuclear weapons. Unfortunately, this was just the latest in a series of misstatements about alliance nuclear policy by President Yoon or senior members of his administration. Taken together, these actions signal increasingly severe friction in the alliance.

Other plans range from forward deployment of U.S. nonstrategic nuclear weapons to the peninsula, offering S.K.’s officials a role in U.S. nuclear deployment planning, or the creation of a nuclear-sharing arrangement that may or may not resemble the one in NATO. The critical feature of all such proposals is that none of them would provide S.K.’s officials with additional information about when, where, and why the United States would use a nuclear weapon on the peninsula. None of these plans would dispel their anxieties.

Toby Dalton is the co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He has presented a helpful taxonomy of the differing logics behind calls for additional nuclear integration within the alliance. Zealots believe that only a nuclear weapon can deter a nuclear weapon. They will never feel secure until a S.K.’s president of their own party has release authority over nuclear weapons. Bargainers may hold real anxieties over extended deterrence. However, they will exploit them in order to extract concessions from the U.S. Populists simply support nuclear proliferation or nuclear sharing as a kind of signal to appear hawkish on foreign policy. Zealots have been dominating the conversation. They have coopted the other groups to push for an indigenous nuclear weapons program or nuclear sharing. Few officials, in S.K. or in the U.S., have confronted this narrative.

This fixation on nuclear weapons is to the detriment of other capabilities. This includes S.K.’s own exceptional conventional defense and deterrence posture. It is corrosive to the alliance. Further increasing the relevance of nuclear weapons cannot address anxieties, only fuel them. If U.S. officials cannot shift the alliance’s attention to nonnuclear deterrence and educate S.K.’s public opinion to support the shift, demand for nuclear sharing and/or nuclear proliferation will continue to increase.

It was in this context that Yoon and U.S. President Joe Biden launched the Washington Declaration in April of 2023. This summit could be considered the swan song of nuclear assurance. It established a new Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG), expanded tabletop war games between the allies on nuclear weapons issues (including with U.S. Strategic Command), and announced a presidential commitment to make every effort to consult with S.K.’s president before using a nuclear weapon on the peninsula. This spring, S.K.’s officials visited the US SSBN base at King’s Bay and the SSBN USS Kentucky sailed to Busan.

Please read Part 3 next

Blog

-

Nuclear Weapons 847 – South Korea Seeks Reassurances About U.S. Nuclear Umbrella – Part 2 of 3 Parts

-

Nuclear News Roundup January 23, 2024

North Korea now using AI in nuclear program: report foxnews.com

IAEA mission reaffirms safety of Fukushima water release world-nuclear-news.com

Belarus and Russia aim to deepen nuclear cooperation world-nuclear-news.org

Halushchenko: Khmelnitsky can become Europe’s most powerful nuclear plant world-nuclear-news.org

-

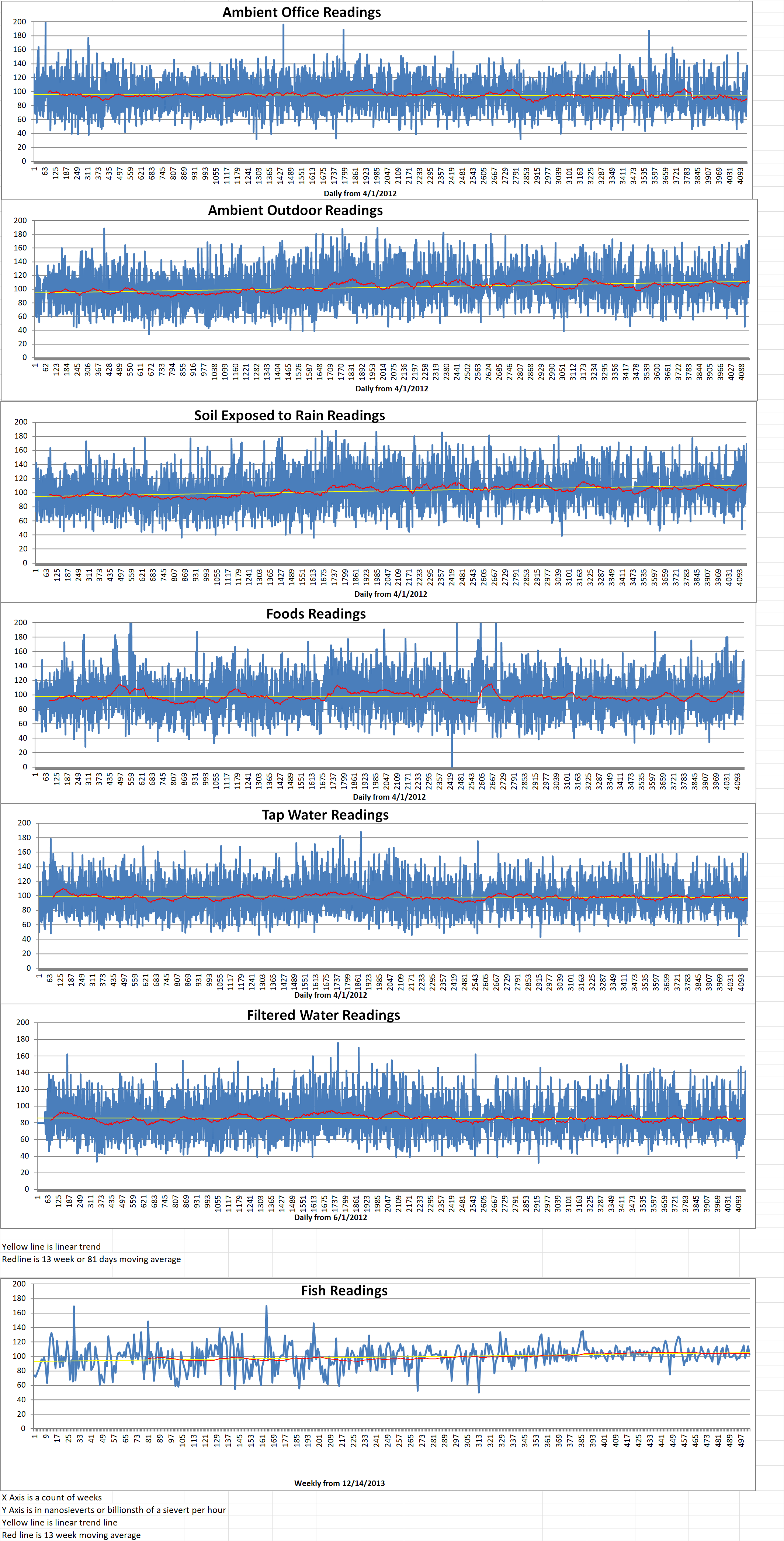

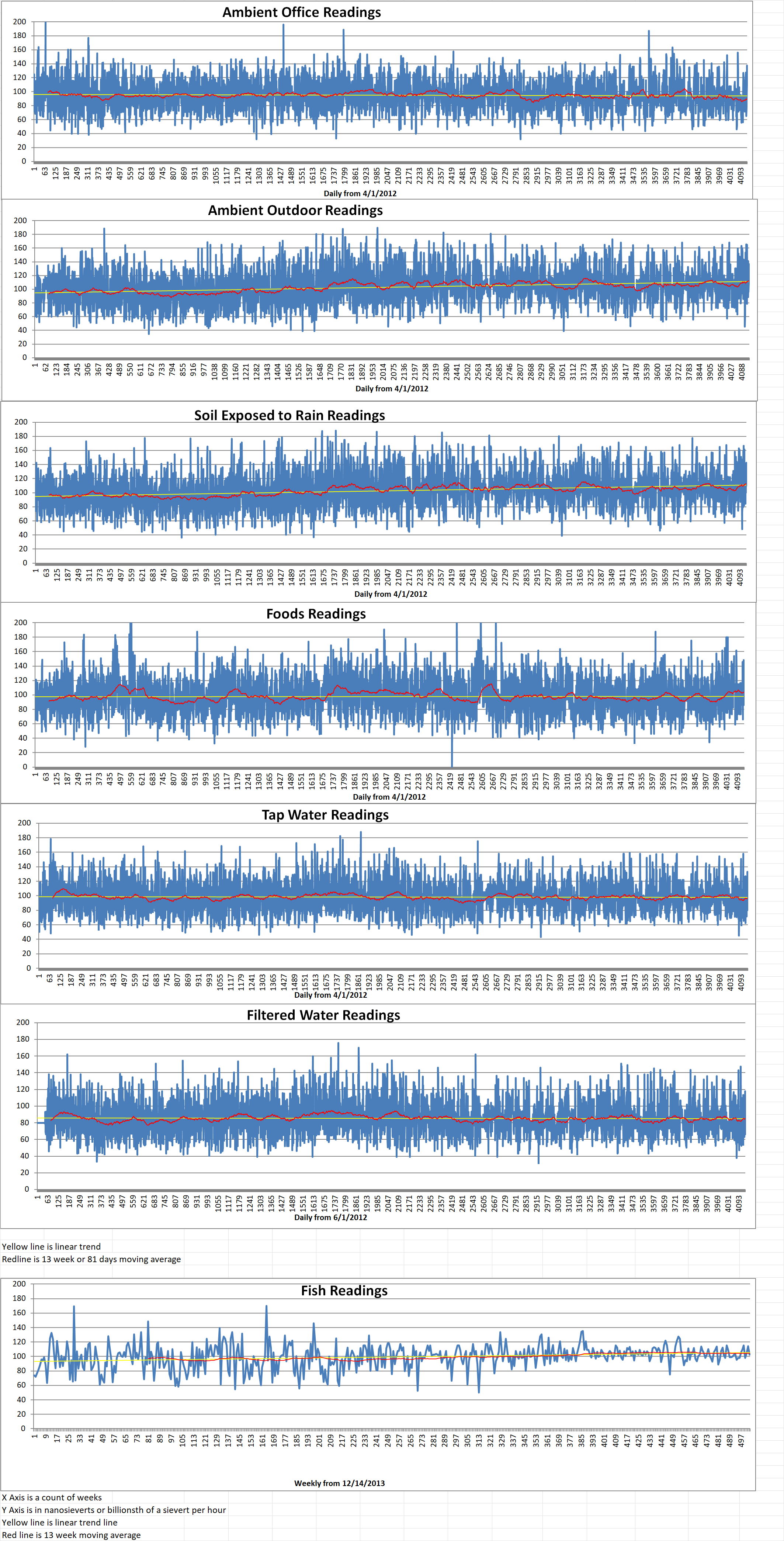

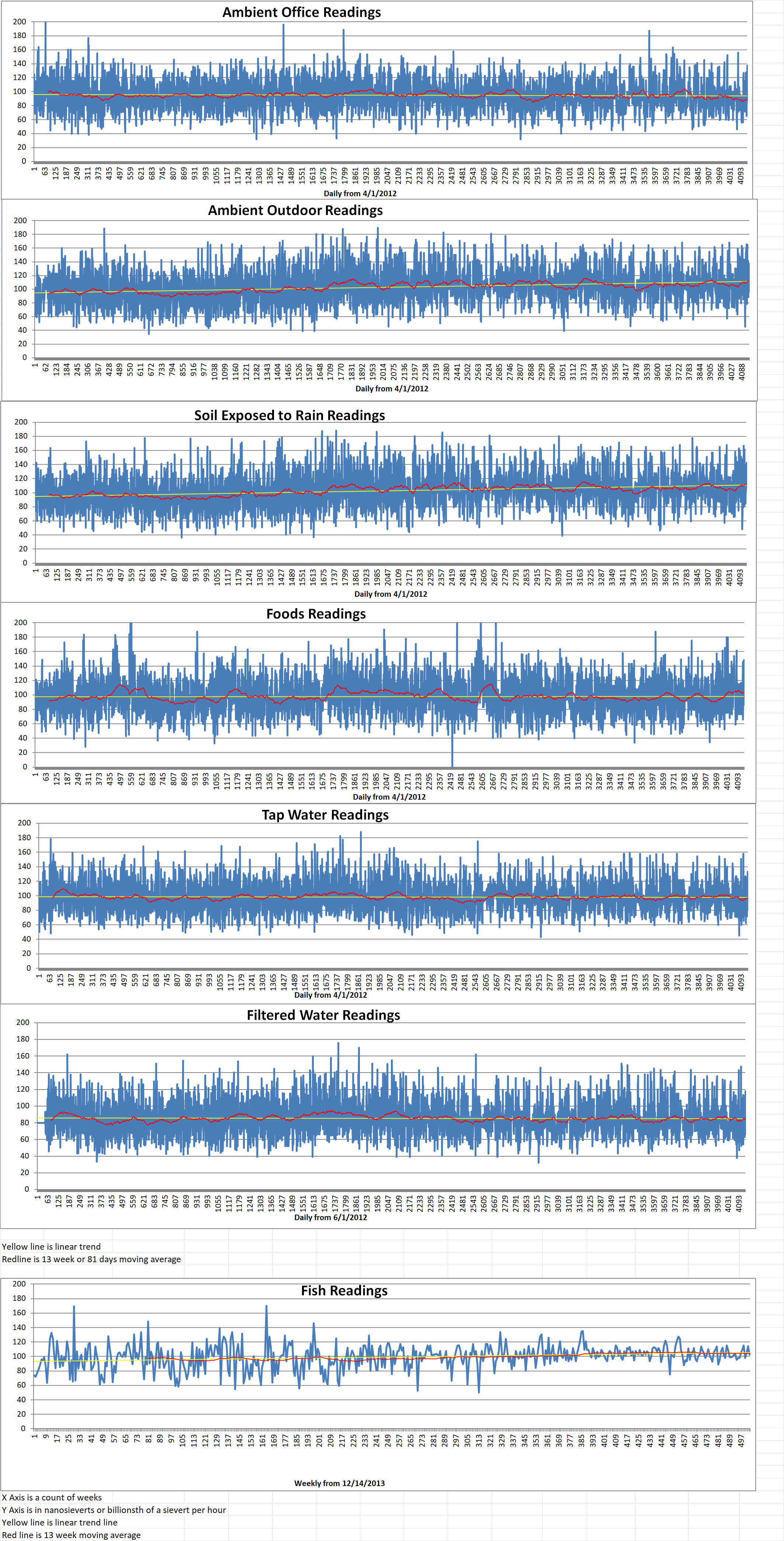

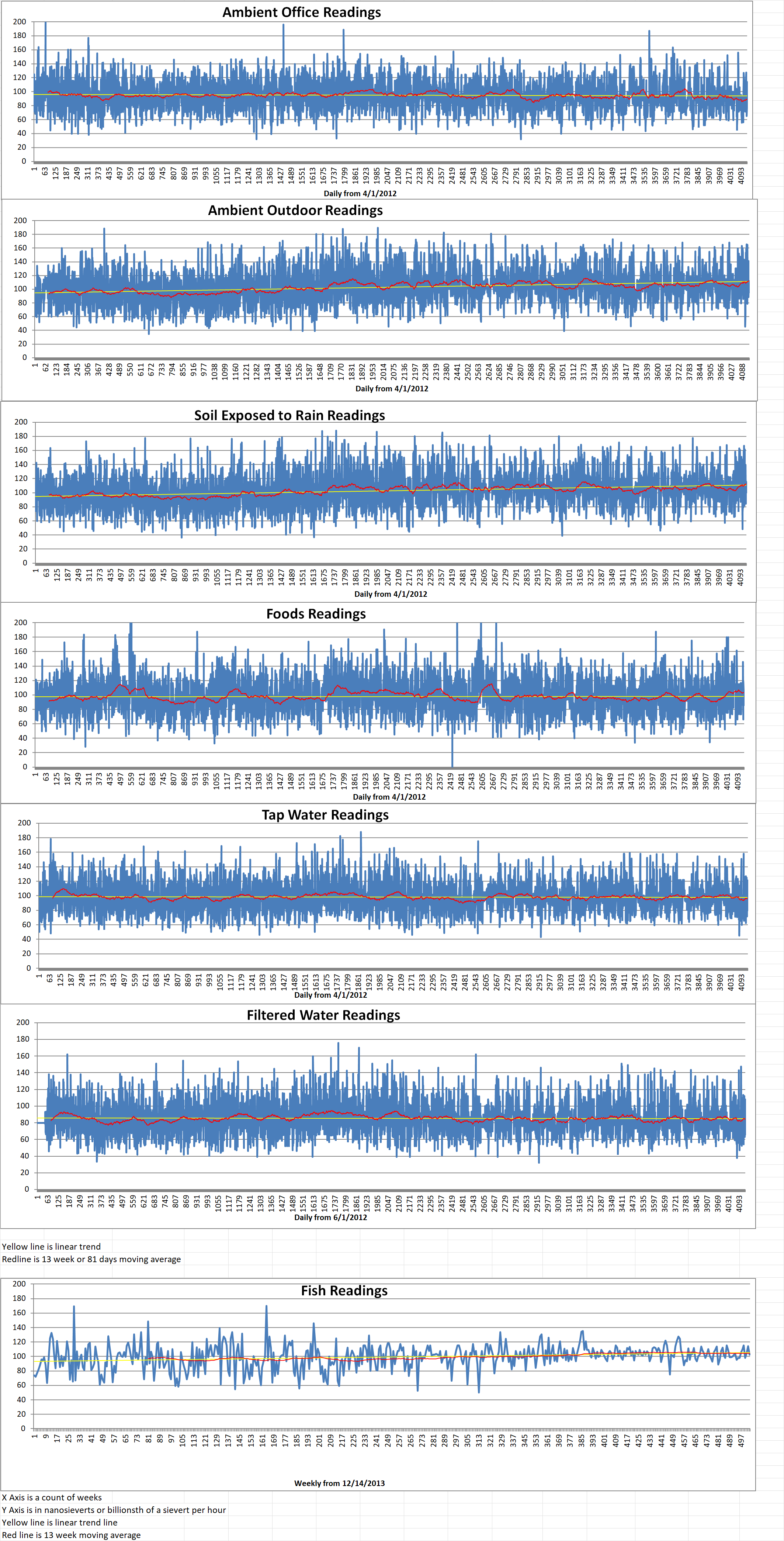

Geiger Readings for January 23, 2024

Ambient office = 114 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 159 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 159 nanosieverts per hour

Avocado from Central Market = 73 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 100 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 90 nanosieverts per hour

-

Nuclear Weapons 846 – South Korea Seeks Reassurances About U.S. Nuclear Umbrella – Part 1 of 3 Parts

Part 1 of 3 Parts

For the last twenty years, U.S. commitment to extend nuclear deterrence over South Korea (S.K.) has faced increasing pressure. During that time, seven North Korean (N.K.) nuclear tests and rapid advancements in a diverse array of advanced missile technologies have forced the alliance to adapt its posture and develop new capabilities and concepts to counter aggression and nuclear first use. For the most part, the alliance has risen to meet this challenge. Improvements in conventional capabilities have tipped the balance of power further south over the same period, providing additional capability not only to deny N.K. the benefits of aggression but also to deter and respond to nuclear use. This is especially true of S.K.’s stand-off strike systems.

The alliance is meeting the military challenge. However, it is failing to manage the political challenge of extended deterrence. Over the last two decades, S.K.’s confidence in U.S. security guarantees has fallen sharply, despite this strong military position. Two trends have placed the alliance in a difficult situation. First, the U.S. commitment to defend S.K. with nuclear weapons has become cancerous, threatening to metastasize and infect other aspects of the alliance. Second, the Trump administration’s statements and actions forced S.K. to confront the problems of depending on an ally that is currently grappling with isolationist authoritarian tendencies.

U.S. defense officials have considered the nuclear extended deterrence as a component of the framework of the nation’s alliance structure. The theory is that extended deterrence assures allies of their own security. This means that they need not consider developing their own nuclear arsenal. The problem is that, because the President of the United States retains sole authority over the use of nuclear weapons, no ally can be certain that the U.S. will use a nuclear weapon in and only in cases when they believe it is a necessity. On occasions when allies express anxiety about depending on U.S. extended nuclear deterrence, U.S. officials usually embark on a round of nuclear reassurance, displaying nuclear-capable systems and holding consultations designed to show allies that they are attentive and committed to their nuclear mission.

Especially in S.K., nuclear assurance not only fails to address allied anxieties, but also fuels them. Existing nuclear assurance mechanisms can establish U.S. capability. However, it cannot prove the resolve of US leaders or provide S.K.’s officials with a reliable expectation about when, where, and why the United States might use a nuclear weapon on the Korean peninsula. Because there is nothing that U.S. officials can do to resolve either problem, extended nuclear deterrence is an unreliable foundation for the U.S-Korean alliance. Even worse, nuclear assurance mechanisms effectively raise the relevance of nuclear weapons, which contributes to a public and elite misperception that S.K.’s security depends on US nuclear weapons, even though this is less and less true as time passes because the alliance’s conventional capabilities continue to improve.

S.K.’s officials and experts have presented a variety of proposals that they believe would assuage their concerns. The current idea is a request that the U.S. commit to use a nuclear weapon in response to N.K. nuclear first use, what we might call automaticity.

Please read Part 2 next -

Nuclear News Roundup January 22, 2024

Russia says return of US nuclear weapons to Britain dangerous mehrnews.com

Doug Ford government to refurbish Pickering nuclear plant as demand for electricity grows cbc.ca

Studies to examine health risks of New England nuclear power plants hsph.harvard.edu

Biden to Offer $1.5 Billion Loan to Restart Michigan Nuclear Power Plant news.yahoo.com

-

Geiger Readings for January 22, 2024

Ambient office = 108 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 112 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 114 nanosieverts per hour

Tomato from Central Market = 108 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 93 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 89 nanosieverts per hour

-

Nuclear News Roundup January 21, 2024

Holtec to get $1.5 bln to restart shuttered nuclear power plant – Bloomberg News xm.com

Nuclear Fuels Reports Positive Drill Results from the Kaycee Uranium Project, Wyoming newswire.com

Ontario plans major nuclear refurbishment to meet growing electricity demand torontosun.com

North Korea continues testing new nuclear-capable cruise missile, conducts 2 tests within a week foxnews.com

-

Geiger Readings for January 21, 2024

Ambient office = 116 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 81 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 79 nanosieverts per hour

Roma from Central Market = 101 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 112 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 100 nanosieverts per hour

-

Geiger Readings for January 20, 2024

Ambient office = 115 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 153 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 148 nanosieverts per hour

Red bell pepper from Central Market = 116 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 126 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 110 nanosieverts per hour

Dover Sole from Central = 103 nanosieverts per hour

-

Nuclear News Roundup January 20, 2024

First new panel in a decade at US waste facility world-nuclear-news.com

Grossi to visit Zaporizhzhia, warns against complacency world-nuclear-news.org

Uranium production process restarts at Langer Heinrich world-nuclear-news.org

Hinkley Point C woes threaten to break UK and France’s nuclear fusion theguardian.com