Blog

-

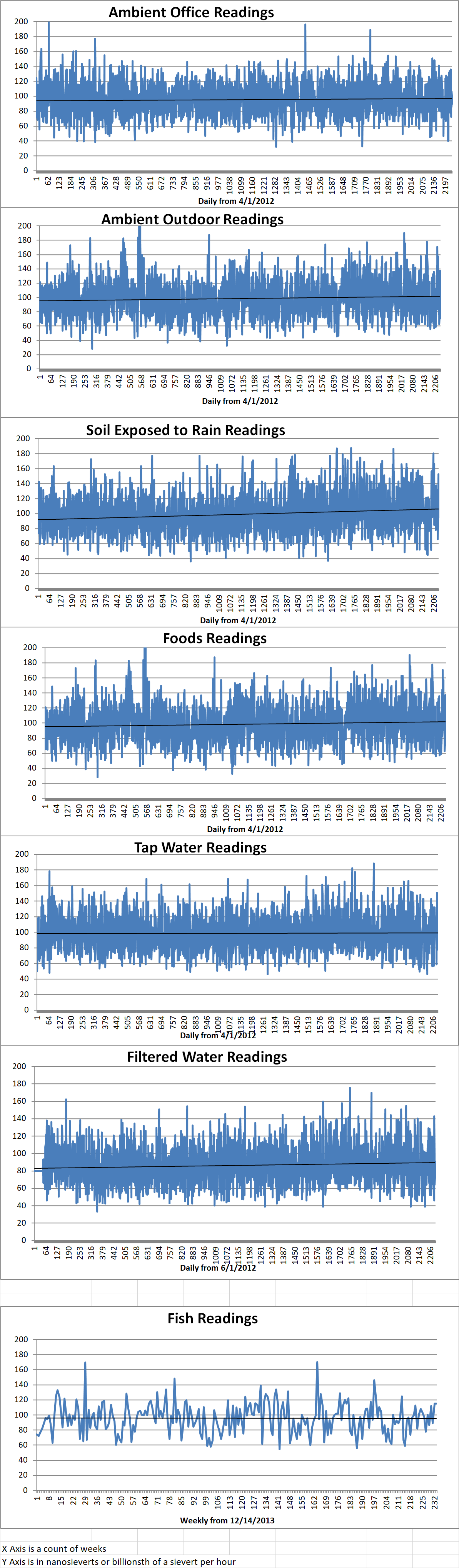

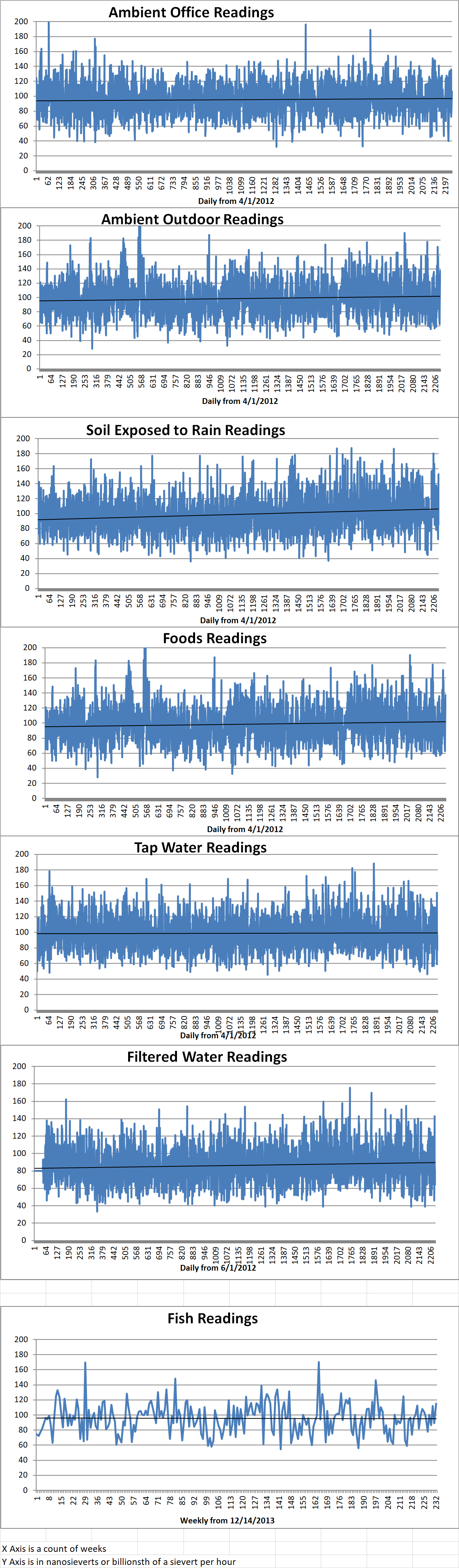

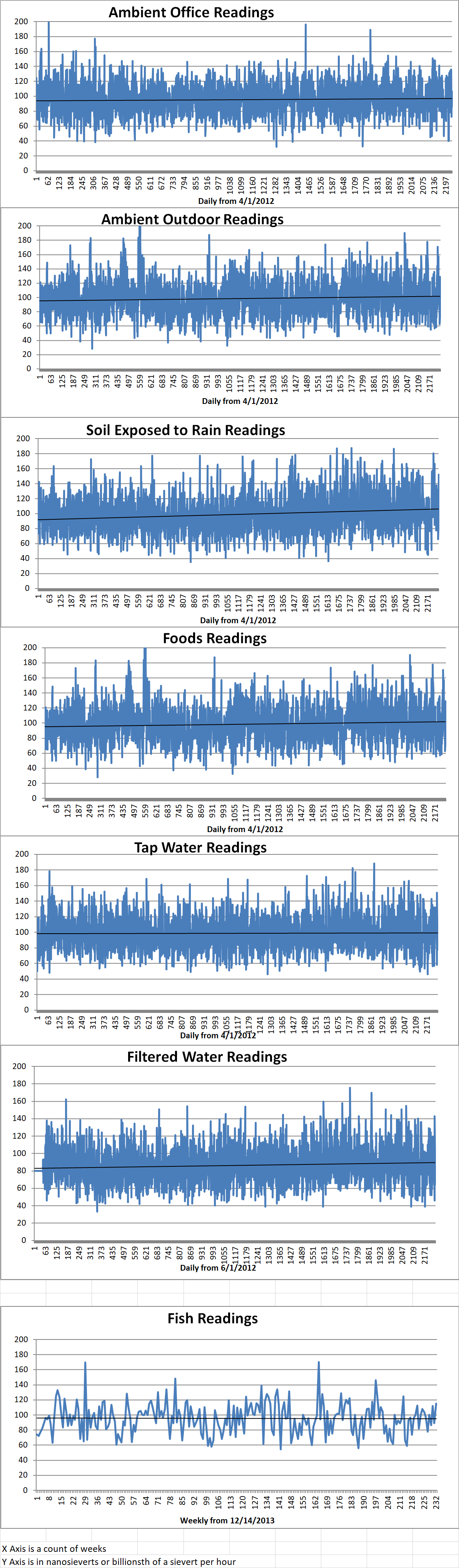

Geiger Readings for Aug 11, 2018

Ambient office = 90 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 100 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 95 nanosieverts per hour

Beersteak tomato from Central Market = 71 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 102 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 91 nanosieverts per hour

Halibut – Caught in USA = 115 nanosieverts per hour

-

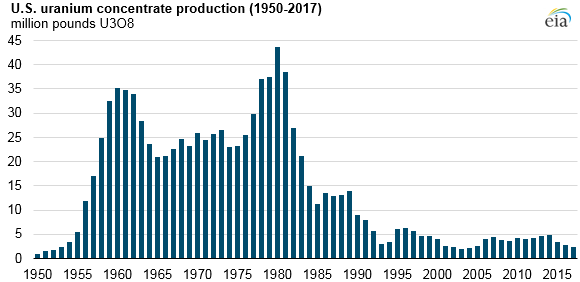

Nuclear Reactors 601 – History Of Uranium Production In The U.S. – 2 of 4 Part

Part 2 of 4 Parts (Please read Part 1 first)

In addition to the competition from the Russian weapons grade ore in the 1990s, a wave of deregulation led to the development of a competitive power market in many parts of the country that would drive nuclear power out of the energy market. In the 1990s, the U.S. government privatized the Department of energy’s uranium enrichment operations. Forty-five thousand metric tons of uranium were transferred to the new private company that was created. In the early 2000s, U.S. uranium production reached its lowest level since the 1950s.

In the early 2000s, the nation of Kazakhstan, one of the old Soviet states, began developing uranium mining. In a few years, it became the biggest uranium producer in the world and the second biggest supplier of uranium to the U.S. market. Kazakhstan was able to increase production so rapidly by using something called “in situ leaching.”

Niger, Mali, Mongolia and Kazakhstan are all currently mining and selling uranium into the international market. They have very lax regulations which allow the in situ leaching mentioned above. It is a cheap method of separating uranium from ore. Toxic chemicals are pumped into uranium mines and uranium is processed from the run off of the leaching liquids. It can be very damaging to the environment and public health. A company spokesman for a uranium mining consultancy said, “Those are countries where their environmental institutions are very weak, their legislation is non-existent, so if you’re competing with in situ leaching in essentially low-governance areas of the world it’s going to be really, really hard.”

In the first years after the turn of the century, the prices for uranium rose. This was caused by declining stockpiles and the fact that interest in nuclear power was on the rise in the U.S. and in developing nations such as China and India. Energy Fuels and Ur-Energy were two private uranium companies that were started during this period. Both companies were started in Canada but they have uranium mines in the U.S. The CEO of Energy Fuels said “I would say at that time it was pretty frothy and in Canada particularly, there was just a lot of venture capital entering the uranium space for investment.”

In 2008, there was a global financial crisis that caused a reduction in the world-wide demand for electricity. During this same period, fracking technology was developed that resulted in a flood of cheap natural gas. This had an adverse impact on nuclear power plans. In addition to cheap natural gas, the rise in renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power made nuclear power even less competitive in the energy marketplace. In 2009, the Department of Energy began to sell excess uranium to pay for the cleanup of a federal uranium enrichment plant.

The nuclear disaster at Fukushima, Japan in March of 2011 caused a tremendous public rejection of nuclear power. Following the disaster, Japan shut down all of its nuclear power reactors. After eight years, they are just beginning to turn them back on. Germany decided to halt the use of nuclear power completely by 2022 and they have pursued the shutdown of their nuclear power reactors as planned in the intervening years.

Please read Part 3 -

Geiger Readings for Aug 10, 2018

Ambient office = 98 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 154 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 153 nanosieverts per hour

Crimini mushrooms from Central Market = 137 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 91 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 80 nanosieverts per hour

-

Nuclear Reactors 600 – History Of Uranium Production In The U.S. – 1 of 4 Parts

Part 1 of 4 parts

I have blogged before about uranium mining and the global uranium marketplace before. Today I thought I would dive more deeply into the uranium mining industry in the U.S.

The U.S. uranium mining industry began around 1955 and flourished during the Cold War until about 1980. The U.S. had generous incentives for uranium mining because it was building up its nuclear arsenal during the Cold War. A uranium market analyst said, “It’s been government-sponsored, government-subsidized just since the beginning. Trying to sort that out and find where there’s a free market in uranium — I find that very questionable.”

The U.S. incentives included a ten -ear guarantee for the price that the federal government would pay for high-grade uranium ore. There was also a ten-thousand-dollar discovery and production bonus for each new ore deposit that was opened. Factoring in inflation since then, the bonus would be almost a hundred thousand dollars in today’s currency. These incentives triggered a uranium “gold rush” in the western states. As one analysist said, “It was crazy around this part of the country. Everyone with a jeep and a Geiger counter was out trying to get rich.”

During the 1960s, the federal government had filled warehouses with enough uranium stockpiles to the extent that the incentive program was not longer needed, and it was cancelled. However, there were rules that stayed in place against the import of foreign uranium until 1975. After that a growing percentage of foreign uranium entered the marketplace.

Inexpensive high-quality uranium ore came from deposits in Canada and Australia. By 1987, the U.S. was importing almost fifteen million pounds of uranium. Domestic production fell by a third to about thirteen million pounds. Although foreign competition did affect U.S. uranium production, the construction boom of commercial power reactors in the 1970s did keep U.S. mines in operation

The meltdown of a reactor at Three Mile Island in 1979 triggered a powerful backlash against nuclear power in the U.S. In 1986, the nuclear disaster at Cernobyl in Ukraine irradiated the country side and caused the permanent evacuation of a Ukrainian city. The U.S. love affair with nuclear power ground to a halt.

During this period, utilities were becoming concerned about the time and money necessary to license and construct nuclear power plants. Actual construction of nuclear power plants fell well below projections for the 1980s. This, in turn, depressed the market for uranium. When the last wave of nuclear power plants came on line in 1990, U.S. uranium production was at a thirty-

five year low.

Following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, it was revealed that the Soviets had been dumping cheap uranium ore onto the U.S. market prior to the breakup. The U.S. put restriction on the import of uranium ore from the old Soviet bloc countries in 1992 which provided some temporary relief for U.S. uranium miners. However, in 1993, the U.S, signed a contract for the Megatons to Megawatts program with Russia to buy five hundred tons of weapons-grade uranium. The high-grade uranium would be mixed with low grade ore to reduce the purity so that it could be made into nuclear fuel for U.S. power reactors. Over the next twenty years, this Russian uranium was used to supply about one third of the fuel for U.S. commercial nuclear power plants.

Please read Part 2 -

Geiger Readings for Aug 9, 2018

Ambient office =100 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 153 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 152 nanosieverts per hour

Carrot from Central Market = 118 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 96 nanosieverts per hour

Filter water = 80 nanosieverts per hour

-

Nuclear Reactors 599 – NRC Is Proposing New Looser Rules For Decommission Nuclear Power Reactors

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has released a regulatory analysis of the regulatory basis supporting a “rulemaking” to change the NRC’s decommissioning of nuclear power reactors. The NRC has multiple goals for changes to the current regulations. First, they want to make the decommissioning process more efficient. Second, they want to reduce the need for granting exemptions to existing regulations. Third, they are going to consider other decommissioning issues that are identified as relevant by the NRC staff. Fourth, they want to support the principles of good regulation, including openness, clarity, and reliability.

The NRC is recommending rule making in the areas of “emergency planning, physical security, cyber security, drug and alcohol testing, training requirements for certified fuel handlers, decommissioning trust funds, applicability of backfitting provisions, and offsite and onsite financial protection requirements and indemnity agreements.”

The revised regulations would “formalize steps to transition a power reactor from operating status to decommissioning while reducing the need for exemptions and license amendments.” There are also recommendations to clarify requirements regarding topics such as spent fuel management and environmental reporting.

In addition to the recommendations for rule making, there are also updates for guidance that deals with aging management, the proper roles for State and local governments in the decommissioning process, the level of NRC review of a Post-Shutdown Decommissioning Activities Report, the options that exist for decommissioning and the schedule for decommissioning.

The regulatory analysis was carried out in order to assess the economic impact on the nuclear industry, government and society that would be the result of the rule making and guidance contemplated by the NRC. The NRC staff laid out the various decommissioning alternatives and discussed the cost benefit analysis. The conclusion is that the staff recommendations for rule making and guidance development is ultimately cost beneficial to the nuclear industry, government and society.

Four Democratic sent a letter to the NRC warning that the new rulemaking and guidance updates could pose a threat to safety, security and emergency preparedness with respect to decommissioning nuclear power plants.

Senator Ed Markey, a member of the Environment and Public Works Committee and one of the four authors of the letter, said “We need a decommissioning rule that acts as a plan for addressing the myriad difficult issues, including the challenges posed by climate change like rising sea levels, that communities will face as nuclear power plants across the country prepare to shut down. The challenge of decommissioning Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant in a safe and expeditious manner would only be greater because of this draft rule.”

“This is a missed opportunity to put down a marker for smarter decommissioning, and I urge the Commission to strengthen this draft rule to ensure safety not expediency is paramount. I will be following up with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to understand why key provisions requested by the public are missing from this proposed decommissioning rule.”

Earlier this year, Senators Ed Markley, Kamala D. Harris, Bernie Sanders and Kirsten Gillibrand co-sponsored legislation to “…improve the safety and security of decommissioning reactors and the storage of spent nuclear fuel at nuclear plants across the nation.” Markley has also introduced the Dry Cask Storage Act. This legislation would require that every nuclear reactor operator comply with an NRC-approve plan that requires that the spent nuclear fuel at a decommissioned plant be safely removed and placed in dry casks storage within seven years of the time that the decommissioning plan was submitted to the NRC.