Part 2 of 2 Parts (Please read Part 1 first)

The two reports mentioned in Part 1 share some important recommendations. These include a consent-based repository selection process and the creation of an entirely new organization to manage nuclear waste disposal.

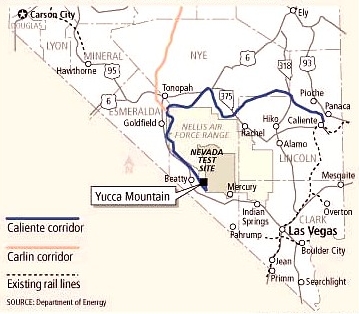

Benson says that it is time for a totally new site-selection process to find a site for a geological repository for nuclear waste in the U.S. Over the past few decades, a great deal of U.S. nuclear waste strategy has focused on the proposed Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste repository in Nevada. The development of this repository was stopped by the Obama administration in 2011 because of stiff local and state opposition. Twelve billion dollars had already been spent by the time the project was canceled. Benson said that this time, the site selection process should be voluntary with local communities having more say as to whether they want a nuclear repository in their neighborhood.

This consent-based approach has worked in other countries, said Ewing. One example is Sweden where communities can veto a nuclear waste project. This dynamic increases the level and sincerity of public engagement and leads to a more successful outcome.

Ewing and Ellis would also like to see the creation of a new organization with the sole responsibility for nuclear waste management. The new organization would implement and coordinate nuclear waste strategy. Ewing said, “When we look around the world at successful nuclear waste programs, this is what works.”

Currently, there is no single group, institution or governmental organization which has the ultimate responsibility for the nuclear waste issue. One result is that there is little incentive to find a viable solution.

Ewing recognizes that the creation of a new governmental organization is a difficult task. He also recommends that the U.S. conduct a comprehensive analysis of the risks and costs associated with keeping nuclear waste in above-ground sites for two hundred years. He said, “At this stage I couldn’t tell you whether nuclear waste disposal is a pressing issue or something that can wait. If there is no harm to doing nothing for 200 years, then that’s very valuable information. If there is harm, then that could become the motivating force that’s absent today.”

Whatever actions that the Biden administration decides to take of nuclear waste, trust and credibility need to be a major consideration, according to the nuclear experts at Stanford. Ewing said, “You can’t use force. That has been tried and it has failed. Unless we mobilize people in a constructive way that really gives voice to everyone’s concerns, I think we will continue to fail.”

Whether it is a new nuclear waste organization, a new consent-based siting process, a comprehensive analysis of the status quo or some other approach, the U.S. nuclear waste strategy should be a collective effort that brings together communities, tribes and states says Ewing.

Ewing said, “My greatest concern is that in 30 years we will be in the exact same position as we are now. The only difference would be that instead of having 80,000 metric tons of spent fuel scattered around the country, we would probably have 140,000 metric tons. That’s unconscionable.”