Scorpius.jpg

Part 1 of 2 Parts

Below the Nevada desert, a machine called Scorpius is being constructed that will utilize high explosives to crush plutonium to states that exist just before a nuclear explosion. The goal of the U.S. two-billion-dollar project is to scan this plutonium with X-rays to help check the accuracy of supercomputer models designed to predict whether the U.S. aging nuclear arsenal will work.

In the first fifty years of the U.S. nuclear weapons program, scientists tested whether the nuclear bombs worked by actually detonating them. In 1992, President George H.W. Bush signed into law a moratorium on nuclear tests.

Currently, supercomputer models are used to predict whether U.S. nuclear weapons might work. However, the accuracy of the models remains uncertain. Scientists do use data from actual explosives for these models. However, these surrogate materials possess significant differences from the plutonium typically used to make nuclear weapons. This raises the question of exactly how well these models simulate real nuclear explosions.

Jon Custer is a technical manager at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He said, “Plutonium is a strange element, displaying six different crystal structures between room temperature and melting, at normal pressure, and a seventh phase at slightly elevated pressure. Three of these crystal structures are unique to plutonium. This means that there is no surrogate material that will truly mimic plutonium behavior.”

Nuclear bombs use high explosives to force weapons-grade plutonium or uranium-235 to implode. This triggers a catastrophic nuclear chain reaction. Scorpius is designed to create nanosecond-long X-ray images of plutonium as it compresses the plutonium or uranium with high explosives. Scorpius took its name from Scorpius X-1 which is the brightest extrasolar X-ray source. The name also reflects its subterranean location where desert scorpions burrow underground.

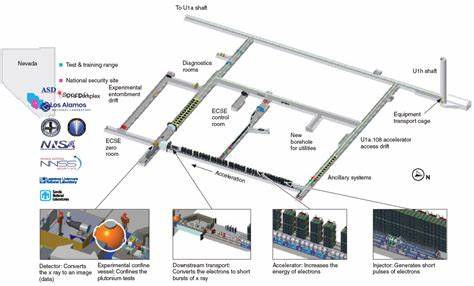

The goal of Scorpius is to help give supercomputer models the accurate data that they require to ascertain whether they are generating realistic simulation of nuclear-weapon behavior. The device is expected to be operational by late 2027. It is under construction a thousand feet beneath the Nevada National Security Site which is a test area bigger than the state of Rhode Island.

Jon Custer is the lead scientist for Scandia’s part of Scorpius. He said, “We will understand the performance and reliability of the nuclear stockpile, a critical part of our national security.” Scorpius is a joint project of the Sandia, Los Alamos, and Lawrence Livermore national laboratories, as well as the Nevada National Security Site.)

Scorpius is specifically designed to “tickle the dragon’s tail” according to Custer. The explosives are designed to bring plutonium to a highly compressed, hot state, but not beyond the critical point at which it would explode.

Custer said, “The conditions in an implosion, even before nuclear yield, are unfathomable to humans. Well before the device would go critical, the temperature inside is well above the surface of the sun, and the pressure is approaching that of the core of the sun. So while we think the models we use are really, really good across such huge changes, we need to test just how good they are. Scorpius allows us to image the real thing. While Scorpius will image late-time behavior, the subcritical experiments are not physically able to assemble into a critical configuration.” Custer also said that there is a long history of experiments bringing plutonium to “subcritical” conditions.

Please read Part 2 next