Radioactive Waste 156 - Penn State University Got A Grant From The U.S. Deparment Of Energy To Work on Spent Nuclear Fuel Recycling

I recently posted a blog about a new process for removing americium from spent nuclear fuel. Today I am going to talk about a new process for removing other highly radioactive elements from spent nuclear fuel. Penn State University recently received a grant of eight hundred thousand dollars from the U.S. Department of Energy a three year research program into reducing the total amount of waste created by nuclear power reactors.

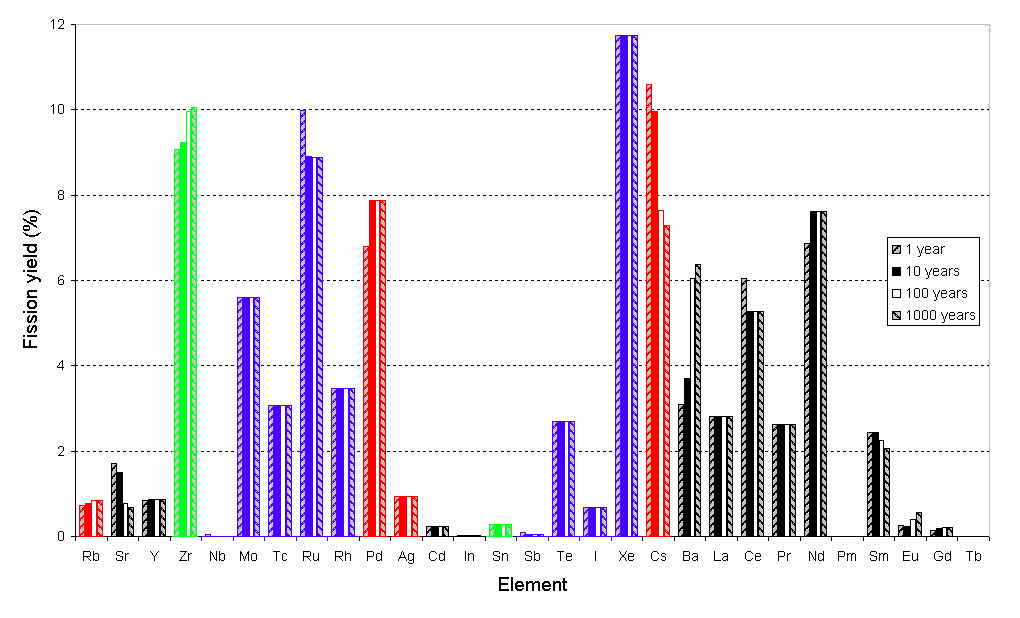

Nuclear fission in power reactors is the most complicated way to boil water ever invented. When radioactive isotopes of heavy elements such as uranium disintegrate, they break into elements with smaller atoms and release enormous amounts of heat. Many of the resulting breakdown products are also radioactive and unstable. They can break down into even smaller elements and emit harmful particles and radiation. Alpha particles are energetic helium nuclei, beta particles are highly energetic electrons and gamma rays are high frequency, high energy photons. High energy neutrons can also be emitted.

Different recycling systems have been invented and tested over the years. The main focus has been on removing uranium for reuse as fuel and plutonium from spent nuclear fuel to be used in nuclear weapons. Other processes are being developed to efficiently remove other elements that are highly radioactive. Cesium and strontium are classified as alkali/alkaline-earths. These elements are very difficult to separate and remove from the rest of the waste. They are highly reactive and tend to form compounds with other elements. The isotopes of cesium and strontium in spent nuclear fuel are the "hottest" elements which generate the most intense radioactivity in the waste. They have a half-life of about thirty years.

A currently popular recycling process dissolves spent nuclear fuel in a solution known as an electrolyte. This permits uranium to be electrochemically isolated and removed. Unfortunately, barium, cesium and strontium interact with other elements in the solution, changing its chemistry to make it more difficult to remove the uranium. One solution to this problem is to continually "refresh" the electrolytic solution. However, this wastes a lot of electrolyte and raised the cost of operations. In addition, the spent electrolytes are mixed with sand and fused into glass in a process called vitrification for long term disposal. The larger the volume of electrolyte to be vitrified, the more complex, time consume and expensive the disposal process.

The electrolytic solution can contain twenty or more different elements. Each of these elements is interacting electrochemically with the other elements creating a very complex situation. The Penn State team is working on electrochemical separation that utilizes electrical fields to physically separate different elements in solution. The DoE is developing a new electrolytic solution specifically to facilitate this new process. The new process will include adding a new liquid "electrode" to the solution. The hope is that this electrically conductive liquid electrode will allow the removal of just the barium, cesium and strontium from the solution. The remaining solution can then be reused. Antimony, bismuth and lead are being investigated for solubility and chemical potential as possible liquid electrodes. The Penn State team will be working with Argonne National Laboratory to test their new liquid electrode.

Elements produced by uranium fission: