Radioactive Waste 216 - Geochemist Claims That Reprocessing Of Spent Nuclear Fuel Would Eliminate The Need For National Repository

I have blogged about the Yucca Mountain Geological Repository before. The federal government decided to build a geological repository for spent nuclear fuel in an old salt mine under Yucca Mountain in Nevada. The project was formally approved in 2002. Preliminary work was done and millions of dollars were spent but the project was abandoned in 2011 by order of the Obama Administration. Meanwhile, spent fuel rods are filling up the cooling pools at nuclear reactors across the country. It is estimated that there will be no national repository before 2050. With the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency, some Republicans officials are calling for restarting the Yucca Mountain project.

A geophysicist named James Conca who is critical of the Yucca Mountain projects says that it was a poor choice for a repository because "the highly-fractured, variably-saturated, dual-porosity Yucca Mt. volcanic tuff with highly oxidizing groundwater was the wrong rock to begin with, causing the cost to skyrocket and the technical hurdles to keep mounting.” He also questions the need for such a repository at all. He said, "The problem this time is that most of our high-level nuclear waste is no longer high level. And most scientists agree we shouldn't dispose of spent nuclear fuel until we reuse it in our new reactors that are designed to burn it."

There are four kinds of nuclear waste in terms of levels of radioactivity. The least radioactive waste is called low-level waste (LLW) and there are six sites around the U.S. that are available for disposal of that type. The next level is referred to as transuranic waste (TRU). The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico is the national repository for that type. Then there is high level waste (HLW) which has no repository. The most radioactive of the types of wastes is spent nuclear fuel which also has no repository.

Conca points out that a great deal of the waste stored at Hanford in underground tanks used to be HLW but over the decades, radioactive decay has reduced it to TRU. That means that it could be safely stored at the WIPP along with other HLW. So there is no need to develop a new repository for that waste.

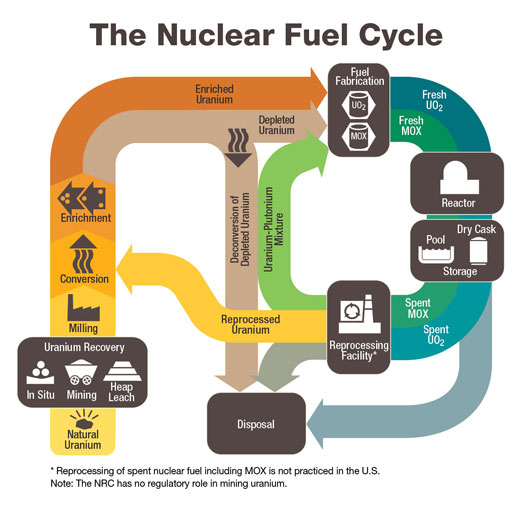

With respect to spent nuclear fuel, there are processes available which can extract useful radioactive materials including plutonium from spent nuclear fuel that can then be used to make fuel which can be burned in some modern nuclear power reactors. Conca says that it makes no sense to go to the trouble of mining and refining uranium for nuclear fuel when spent nuclear fuel can be reprocessed and burned in reactors. He says that if facilities are built to reprocess spent nuclear fuel, then it will be unnecessary for the U.S. to take the time, money and effort to build a new permanent national geological repository for spent nuclear fuel.

Critics of reprocessing proposals point to expensive failures in attempts to establish reprocessing facilities over the years both here and abroad. And the are major questions about the ultimate cost of such reprocessing which might require government support. Non-nuclear weapons proliferation activists point to the fact that reprocessing facilities could create weapons-grade plutonium from spent nuclear fuel.