There are 80 damaged spent fuel assemblies leaking radioactive materials in Fukushima storage pools. enenews.com

The Nucleotidings Blog

The Nucleotidings blog is a writing platform where Burt Webb shares his thoughts, information, and analysis on nuclear issues. The blog is dedicated to covering news and ideas related to nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and radiation protection. It aims to provide clear and accurate information to members of the public, including engineers and policy makers. Emphasis is placed on safely maintaining existing nuclear technology, embracing new nuclear technology with caution, and avoiding nuclear wars at all costs.

Your Host: Burt Webb

Burt Webb is a software engineer, science geek, author, and expert in nuclear science. Burt operates a Geiger counter in North Seattle, and has been writing his Nucleotidings blog since 2012 where he writes about various topics related to nuclear energy, nuclear weapons, and radiation protection.

Burt Webb has published several technical books and novels. He works as a software consultant.

Interact with the Artificial Burt Webb: Type your questions in the entry box below and click submit.

Example Q&A with the Artificial Burt Webb

Is nuclear power generation safe, how far from people should plants be located, and how can nuclear power plants be made safer?

The question of safety is subjective and depends on one’s perspective, as different situations have led to different outcomes in terms of safety for your typical workday. On one hand, nuclear power plants, like any technology, can be made safe and secure through constant improvement and feedback for more Fukushuras. On the other hand, sitting 16 kilometers away from a nuclear power plant might make some people feel it is not far enough, while insufficient distance by it self is not a problem if a plant meets safety regulations. Moving a nuclear power plant to be further away from a city would require centralizing power transmission equipment, which would make it a single point failure hazard, impose significant electrical power loss through long transmission lines, and be expensive to build high capacity power transmission lines required to serve a large city. Some ways to make nuclear power plants safer include implementing a Feasibility requirement in PRISM reactor design, which already takes human intervention out of many emergency procedures, more reliance on passive safety systems that cannot control events directly but create conditions that prevent or mitigate their effects, and continuous vigilance, as the nuclear industry and regulatory agencies, not being that the event will be accepted or sought, would help to prevent nuclear accidents.

What do you mean by “Fukushuras”?

“Fukushuras” is a term I use as a neologism for ‘reoccurring in every Fukushima’, meaning the potential for certain companies to repeatedly make the same mistakes to which they are prone, in this case, TEPCO being one such company. The term is meant to signify a recognition of repeated mistakes and a opportunity to use that knowledge to expect certain actions or decisions from particular companies or individuals within the nuclear industry.

There are 80 damaged spent fuel assemblies leaking radioactive materials in Fukushima storage pools. enenews.com

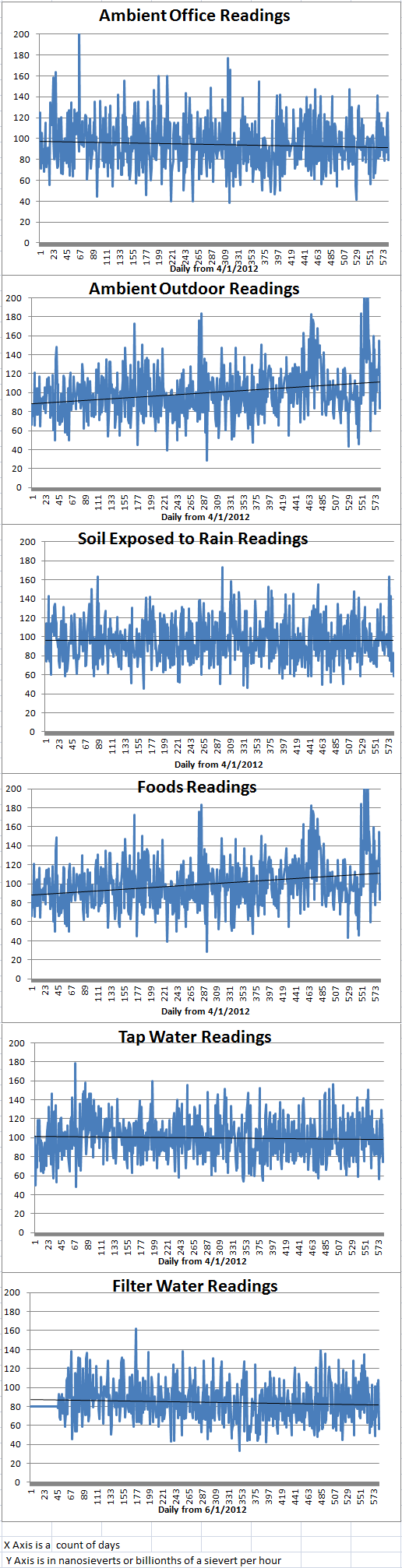

Ambient office = 79 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 81 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 58 nanosieverts per hour

Romaine lettuce from Top Foods = 84 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 74 nanosieverts per hour

Filtered water = 57 nanosieverts per hour

Chief Arvol Looking Horse spoke at the U.N. about Fukushima crisis and threat to future of humanity. enenews.com

Ambient office = 125 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 74 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 83 nanosieverts per hour

Mango from Top Foods = 155 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 115 nanosieverts per hour

Filtered water = 108 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient office = 118 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 96 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 79 nanosieverts per hour

Iceberg lettuce from Top Foods = 133 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 102 nanosieverts per hour

Filtered water = 91 nanosieverts per hour

And now for something entirely different! Today we leave the Middle East and return to the site of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the Ukraine. In 1986, a power surge triggered an emergency shutdown of the reactor. A huge spike in power to the reactor resulted in a rupture of the reactor vessel and releases of steam. Ultimately, the moderator rods caught fire and huge plumes of radioactive smoke were released into the atmosphere. The plumes drifted over Europe, dropping radioactive fallout. Over half a million workers were deployed to deal with the emergency and cleanup. At a cost of billions of dollars, the reactor was entombed in a giant concrete shell and the surrounding cities and countryside were abandoned. Tests at the Chernobyl site show that the level of dangerous cesium-137 has not been dropping as rapidly as estimated. It was thought that half of the cesium would be gone in the twenty seven years that have passed but that is not the case. Scientists are unsure of why the site is still so radioactive.

Recently a robot was sent into the reactor to check conditions. The operators of the robot were astonished to find black slime growing inside the reactor vessel. The level of gamma rays (highly energetic photons) inside the reactor is very high and it had been assumed that nothing living aside from a particularly radiation resistant bacteria could survive and grow in such an environment. The robot brought a sample of the slime out of the reactor for examination.

The slime turned out to be composed of several types of fungi. In the lab, the slime grew faster when the gamma radiation was raised to five hundred times above the normal background level of gamma radiation. The reason that the slime was black is that it contained high levels of melanin which is a dark pigment found in many animals. It is the primary determinant of skin color in human beings. It appears that the slime is using melanin to extract energy from the gamma radiation in a way similar to the use of chlorophyll in plants to use the energy in visible light to power biological processes. When a gamma ray hits a melanin molecule, its structure is altered and the slime is able to use the energy released in the reaction.

The reactor at Chernobyl is going to be enclosed in a steel dome to prevent further release of radiation into the environment. The slime might be able to continue to grow because it is not dependent on sunlight for energy. There is some concern that the slime could spread beyond the Chernobyl reactor and possibly pose a threat to plants and animals around the reactor. Life is tenacious and some forms thrive in very hostile environments. Even so, the discovery of this slime living in a highly radioactive environment is surprising.

Chernobyl power plant after the accident:

Fukushima cleanup workers fear for their own safety. enenews.com

The last delivery of downblended Russian uranium is making its way to the United States as the Megatons to Megawatts program draws to a close next month. nuclearstreet.com

Luminant to quit efforts to license two nuclear reactors announces big win for nuclear opponents. yournuclearnews.com

Ambient office = 87 nanosieverts per hour

Ambient outside = 62 nanosieverts per hour

Soil exposed to rain water = 71 nanosieverts per hour

Meican Hass avacado from Top Foods = 118 nanosieverts per hour

Tap water = 130 nanosieverts per hour

Filtered water = 104 nanosieverts per hour

Today, I am continuing with nuclear matters in the Middle East. Recently I have been blogging about Iran. This blog is going to discuss Iran’s nuclear program. The U.S. began helping Iran with nuclear research from the 1950s. Iran established the Tehran Nuclear Research Center which was run by the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran. In 1967, the U.S. provided Iran with a research reactor. In 1968, Iran signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation treaty which included inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The Shah of Iran was very interested in nuclear power because he knew that the oil under Iran would run out some day.

Construction of the Bashehr I nuclear plant was started with German assistance in 1975 at a site near the city of Bashehr on the Iranian Persian Gulf coast. In addition, uranium processing facilities were built with the assistance of foreign companies and governments and deals were signed for uranium supplies. The Shah created a secret program to develop nuclear weapons. U.S. assistance stopped when the Iranians overthrew the Shah’s government in 1979. International assistance in uranium enrichment was halted and as was work on the Bashehr reactors.

The Iranian secret nuclear weapons program was disbanded by the Ayatollah Khomeini when he took power after the revolution. He said that Muslim ethics and jurisprudence did not allow for the creation and use of nuclear weapons. Iran has signed international treaties that outlaw the use of weapons of mass destruction including nuclear weapons. Research and development on the use of nuclear energy to generate power continued under Khomeni. By 1988, the Iranians had opened ten uranium mines inside of Iran.

Around 1990, the Russians formed Perspolis, a joint research organization, with the Iranians. Despite intense international pressure the Russians continued to help the Iran with nuclear research and development through the 1990s. A Russian contractor was retained in 1995 to resume work on the Bashehr I power plant. Problems with cost overruns, technical issues and international pressure interfered with the completion of the plant. Finally, in 2010, nuclear fuel was delivered to the reactor and the plant began generating electricity in 2011 for the Iranian power grid.

The IAEA conducted inspections during the 1990s and found that the Iranians were in compliance. Their research and development they were conducting was aimed at the peaceful development of nuclear energy for electricity. Despite IAEA reassurances, the U.S. and its major allies continued to fear an Iranian nuclear weapons program.

In 2002, Iranian dissidents claimed that Iran was working on an underground uranium enrichment facility and a heavy water reactor called Arak. The IAEA demanded access to these sites so it could carry out inspections. Through the first decade of the Twenty First century, There were a number of diplomatic initiatives launched by major industrial nations as well as Iran itself that sought to create frameworks that would allow the Iranians to continue working on nuclear power generation while reassuring the foreign powers that Iran would not develop nuclear weapons. During this period, Iran broke many agreements with the IAEA for full access to nuclear sites in Iran or failed to abide by agreements to halt uranium enrichment. Trade sanctions were initially imposed by the U.N. in 2006 to interfere with Iran’s nuclear program. Subsequently, harsher trade sanctions were imposed on a wide array of products including consumer goods. In spite of these efforts, the IAEA cannot be sure that Iran is not working on nuclear weapons development.

Once again, in 2013, there are negotiations underway to get Iran to stop enriching uranium and to get them to stop construction of a heavy water reactor that might be used to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons . Russia and Iran recently announced a project to build a second nuclear power reactor in Iran. As I have reported before, Israel is very concerned that Iran will have nuclear weapons unless military action is taken soon. Saudi Arabia might also obtain nuclear weapons if Iran is known to have them. I am afraid that the situation in the Middle East is very unstable at the moment with respect to nuclear weapons.

Bashehr nuclear reactor model: