Part One of Two Parts

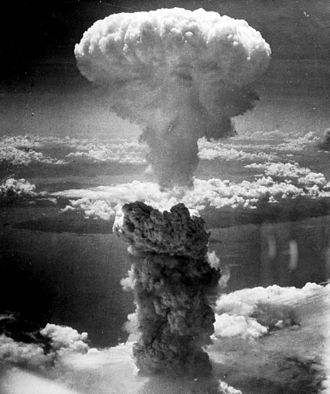

There has been a lot of press lately about nuclear disarmament. The U.N. recently held a big meeting to discuss the global situation. I decided to dedicate this blog post to a bit of the history considering the possible use of nuclear weapons. The United States dropped one nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, Japan and one on Nagasaki, Japan in 1945 at the end of World War II, securing the surrender of Japan. There have been arguments that such an action was necessary to end the war and counter arguments, that we could have defeated Japan without dropping those bombs. The devastation caused by single bombs to those Japanese cities was so thorough and horrifying that the world entered a new phase with respect to the possible use of these new weapons.

The U.S. built up a nuclear arsenal after the war. The U.S. nuclear doctrine was put forth by the U.S. Secretary of State in 1954. The U.S. said that it was not interested in developing a first-strike capability to destroy an enemy in a surprise attack but rather the capability for massive retaliation. The big strategic concern at the time was the possibility that the Soviet Union might invade Western Europe with conventional forces. The U.S. wanted the Soviets to understand that if they attempted such an action, the U.S. would destroy them with nuclear warheads. A major reason for this doctrine was the fact that the Soviet conventional forces were larger than the U.S. and its European allies combined.

In the early 1960s, powerful groups in U.S. politics led by the RAND corporation, an influential think tank with close connections to the U.S. military, began to attack the U.S. nuclear doctrine as being too "defensive." These groups wanted the U.S. to see nuclear war as a legitimate military strategy and insisted that the U.S. make preparations for prosecuting and winning a nuclear war. False alarms were raised that the Soviets had built up a nuclear capacity greater than the U.S. and the U.S. had to act decisively to close this fake "missile gap." Massive amounts of money were spent on building up stockpiles of U.S. nuclear warheads and delivery systems.

Henry Kissinger wrote "Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy" and Herman Kahn wrote "On Thermonuclear War". These two influential books argued that a more "active" and aggressive U.S. nuclear doctrine was needed to defend the national security of the U.S. They claimed that:

"1. Nuclear war is possible.

2. A nuclear war can and should be won, although a new definition of the level of ‘acceptable losses’ is needed. For Kahn even 40 million dead Americans would have been ‘acceptable losses’. (At that time the U.S. had a population of 200 million.)

3. A nuclear first strike capability would enable a disarming surprise attack, thus limiting the retaliation possibilities of the adversary.

4. Limited nuclear war should be part of military strategy (this last point wasn’t really new, since, during the Taiwan Strait crisis, Eisenhower threatened to use nuclear weapons as ‘bullets’ to destroy Chinese army bases)."

Kissinger and Kahn discussed different scenarios of nuclear war and included tables listing the possibilities for the number of immediate dead, the number of mid-term dead, the number of dead from long-term suffering, the number of injured, the number contaminated with radioactivity, and those who would survive unscathed. They also covered the expected damage caused by radiation and other deleterious effects of nuclear war. There was even the suggestion that the elderly be fed contaminated food supplies because they would not live long anyway.

Kahn suggested that forty million deaths (one fifth of the U.S. population at the time) would have been "acceptable" to win a nuclear war. He estimated that it would take twenty years for the U.S. to recover from the damage of Soviet retaliation. Many critics of Kissinger and Kahn were horrified by the calm tally of horrors in their books.

(See Part Two)

Nuclear explosion that destroyed Nagasaki, Japan: